Earlier in December, Meta started testing ActivityPub with Threads, marking the start of a long-promised integration with the Fediverse - one which many were sceptical would ever arrive. To say that reactions to this were mixed would be a rather extreme understatement: to an external observer, though, the number of existing Fediverse users who were less-than-welcoming to the presence of Threads, to say the least, might seem strange. After all, to have a social media giant come onto the same federated protocol and offer people an easier way of taking part should be great, right?

If you work in or around technology, you’ve probably heard of the old Microsoft phrase “embrace, extend, extinguish” - and I think it’d be fair to say that there is a degree of concern around that happening. After all, this did play out before with XMPP - Google Talk, Skype, AIM and even Meta’s own old Facebook Chat all built support for that open and extensible protocol, then all dropped it, and you’d be hard pressed to find many modern XMPP users now - though in fairness, ActivityPub usage is probably higher now than XMPP usage ever was before major brand adoption, especially considering recent turmoil on the ex-birdsite X. Yet, to reduce the concerns to E/E/E ones - or even to suggest those were the largest ones - would be to deeply misunderstand where a lot of people are coming from.

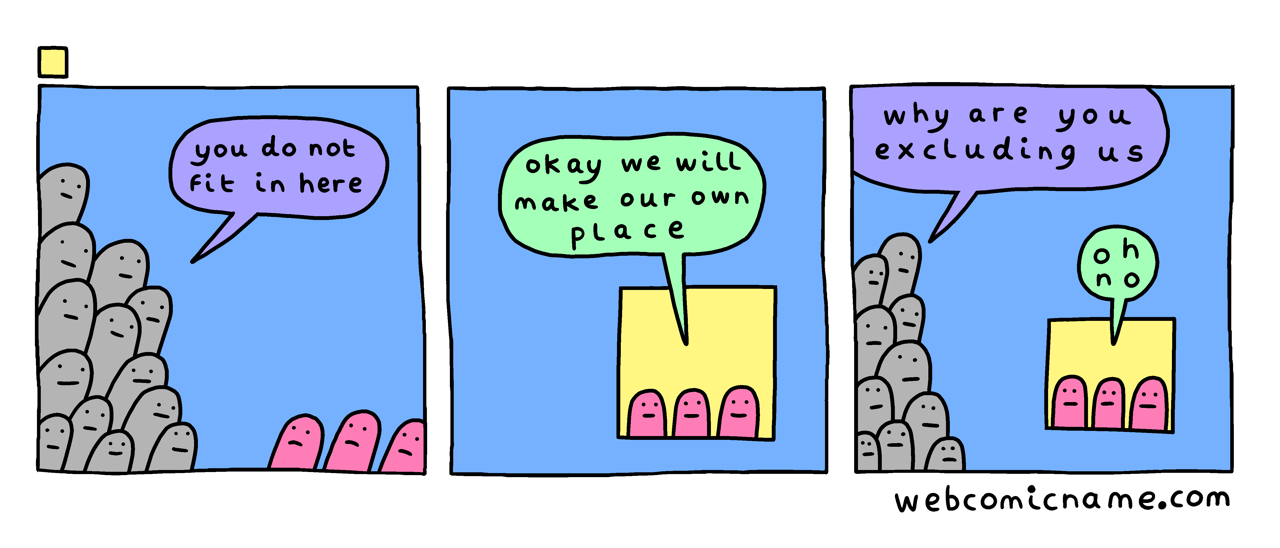

The vast majority of popular, mainline-federated Fediverse servers are run by people with a socially liberal and progressive outlook on the world. Don’t get me wrong, I very much include myself in that list! The ultimate consequence of that is that “fedi” has become a space that queer and marginalised people have made home - and a deliberately “weird” home at times too - so, understandably, when mass waves of adoption come, that poses a real threat to that cosiness, queerness and “weirdness”. Again, this fear hasn’t come out of nowhere, but is in practice extremely common when it comes to spaces that start as queer-only - both online and in the real touching-grass world too. Alex Norris’ “webcomic name” is so often excellent at summarising these kinds of things:

Part of the question then becomes “well, what is social media - and does it matter who it connects?“. Whilst some platforms are designed around solely interacting with those you already know, most social media platforms are designed around the concept of being able to share content with others you might not yet: and therein lies the rub, because the matter at hand is then who the people you don’t know yet are. For so long as there are those in society who would seek to punch down - for so long as there are people that are racist, sexist, transphobic, homophobic, whatever it happens to be - there will be people who interact with those biases and prejudices online, depressingly. There’s only three real ways around that problem: allow-list only those you know are good actors, be small enough that bigots have no reason to trouble you, or have comprehensive and meaningful moderation with a set of common norms that at least the folks on one server can all agree on and sign up to. And, for what little it’s worth, I’d argue that the first two are no longer really an option for a Fediverse that wants to be genuinely federated and open.

The fundamental challenge here is that code can’t fix society. For as different as the people absolutely are, the sentiment that it can is one absolutely shared between a lot of “tech bro”-types and a lot of folks on the left too: there’s a kind of sweet but, depressingly, baseless optimism that a particular innovation or set of innovations will fix things and will allow people to deal with far fewer or even no issues with their interactions between individuals. There’s plenty of people out there who already have the intention to bully, harass and intimidate others - whether you make it marginally easier or harder for them to do so is almost completely moot to whether they achieve that mission. Ironically, it’s the federated nature of the Fediverse which makes this so inevitable: a platform where your users are all vetted, or even where they’ve all come to a single shared space, would reduce these risks hugely, but it would also defeat the object of the Fediverse’s technology to at least some substantial degree, and would limit the ability of users to genuinely participate when they’re self-hosting their own instances. Were the Fediverse to continue to grow without federating with Meta, these bad actors would still come - indeed, plenty are already present (read the #fediblock hashtag at your peril) - it’s just we play whack-a-mole more often trying to find them.

based on Cosmocatalano's CC0 "pick any two" Venn, via Wikimedia Commons

Don’t get me wrong, this isn’t me saying “well, technical change is meaningless, so we shouldn’t even try”: nudges are powerful at dealing with some specific challenges. Twitter’s old “Most people don’t Tweet like this” box is a really prominent example of where a small technical change might have a meaningful impact for someone who was just having a really bad day, wanted to let off steam, and poorly chose to let it off directed at someone. Likewise, I’m sure that Mastodon’s restrictions on quote-Tooting could, for some people, in some cases, dissuade abuse and encourage conversation. But the blunt reality is that we as technologists have to accept the limits of our own reach and power: much as we might like to convince ourselves otherwise, we are never going to be able to remedy society’s ills on our own. Dealing with social problems is always a multidisciplinary task - which, yes, may involve technical nudges, but also involves a hell of a lot of campaigning, discussion, engagement and extensive community working. Slapping a few lines of code into a GitHub repository will never replace any of that.

A larger Fediverse was always going to be a more fragmented Fediverse. And, for what it’s worth, I feel like that’s kind of okay. Nowhere in anyone’s vision here was originally the idea that federation would somehow lead to everyone getting along with one another, so it’s sort of a red herring to be chasing that: if one instance wants to defederate with another, or if one set of them want to block Threads or any other way of accessing federation that does involve a higher risk of seeing abusive content, that’s their choice - and a choice that should be valued and respected as entirely theirs to make. Equally, if others want to take on board the risks involved in federating to an actor that’s acknowledged to have substantial potential ethical and moderation issues, that doesn’t imply they’re endorsing the platform, or that they’re ignoring the potential dangers - it just means they choose to draw their lines for community risk appetite somewhere different. That, right there, is the joy of locally autonomous community decision-making - you get to choose where you want to stand on all these issues as a local community yourselves, in a way that you would simply never have an opportunity to do on a closed platform.

Different people will choose to pick different sides of that weird Venn-triangle from earlier, and that’s okay - because for some, the safety of their space is most important, and for others, reach and community openness is most important. For so long as people have a genuine, free and open choice as to which instance they want to be part of and which bit of those lines they land in, there’s no right or wrong answers there. In any event, personally, if people are offered a choice between moving to a Meta-based platform to talk to people they know, or using an independent federated platform to talk to people they know who are still using Meta-based platforms, I’d rather the latter than the former wherever possible.

The Internet is great because it allows everyone to be connected, not because it forces everyone to be. It’s okay to not like everyone, and to not agree on everything all the time: we form local communities online just like we do offline. Tech doesn’t magically make us all best friends - nor does it magically remove the people who threaten or abuse us offline - but we shouldn’t have ever expected it to.

Social media won’t save us from corporations, from each other, or from the perils of the real world. The communities we build through it can, though. Value people over tech, and the connections we build over the way we build them, and you end up with something that lasts.

Postscript: After writing up my initial draft of this post, I read Erin Kissane’s recent post “Untangling Threads”, which dives deep into the complex challenges posed by federating with actors like Threads who are, to put it exceptionally mildly, ethically difficult. It’s an excellent, fascinating and thought-provoking read - especially if you’re an instance admin, I strongly recommend reading it.